In a recent guidance paper regarding risk appetite and tolerance, the Institute of Risk Management highlighted the importance of the question:

“Do the executives understand their aggregated and interlinked level of risk so they can determine whether it’s acceptable or not?”

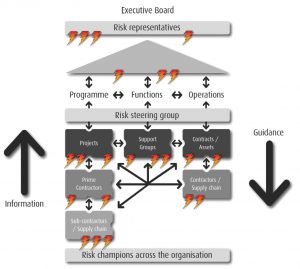

Good risk management means getting the right risk summary information to the right people at the right time and gaining appropriate management attention. Deciding how to construct this summarised risk information can be a major challenge across large, complex organisations.

Even if you have a good risk process in place, as the person responsible for Enterprise Risk Management (ERM), you are faced with the overwhelming challenge of distilling large amounts of risk data from many different sources within the organisation into a comprehensible story that can be communicated to any part of the organisation. As the person responsible for drawing management attention to the key risk areas, you will need a risk map to help achieve this. The risk map should be aligned with objectives and define the key criteria that are used to identify, aggregate, communicate and respond to risk.

Figure 1: Five steps to ERM

The Chief Risk Officer, working closely with senior management, is responsible for ensuring that the risk map is defined and implemented across the organisation. The task of refocusing risk management from a tactical to a strategic exercise then becomes far less onerous. The journey to ERM will be bolstered by major cost savings to be made by implementing high-level risk management activities, rather than duplicating risk response activities across the organisation in a disjointed way.

This white paper, third in a series on implementing Enterprise Risk Management, is written for those people responsible for making sense of the risks across an organisation, interpreting data and turning it into information for making decisions. It offers practical advice on creating the right risk map for your organisation, and helps you to understand the benefits of using it to support your enterprise risk initiative.

The challenge

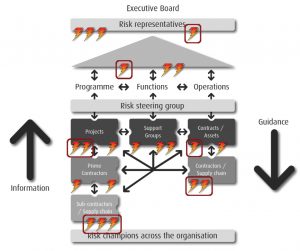

In steps one and two of the five steps to ERM, we offered advice on setting up a risk management framework and policies, as well as an organisational reporting structure. These laid the foundations of ERM by establishing who is responsible for different types of risk within the organisational structure.

With this structure in place, the next challenge is to move from managing risks tactically to managing them strategically. However, you have potentially thousands of risks scattered across the organisation, all with varying degrees of completeness, consistency and quality.

As the person responsible for implementing ERM, you must find a way to make sense of all these risks – somehow they need to be summarised, reported, and communicated.

The aim is to get an understanding of where the risk hotspots in the organisation are. A risk hotspot can be an area of negative exposure to threats, or a source of opportunities. Either way, it requires management attention, action and allocation of resources. A risk hotspot can include unacceptably large risks, serious systemic risks, or related risks that have a knock-on effect across the organisation.

As it stands, trying to get a summarised picture of the ever-changing risk landscape can feel like an insurmountable challenge. How on earth do you make sense of this risk data, and then ensure that the key risk hotspots are strategically monitored and managed?

This is the challenge we aim to address in this white paper.

The risk landscape

Above we referred to an ever-changing risk landscape, and it can be useful to think of the risks overlaid onto the organisational structure as a sort of landscape. Though the risk landscape isn’t a physical one, you can quickly start to see the similarities.

Maps are the most common method used to represent landscapes. Most importantly, people use different types of maps to help make a wide range of decisions. For example, the London Metropolitan Police have mapped out a crime-rate landscape to identify hotspots for key types of crime to help target their resources.

A map can be regarded as a representation of a landscape using symbolic depiction. It can indicate key themes and features of the landscape. The symbolic element is important, since it provides a consistency to the way certain types of features are represented.

Take for example, a journey across the United Kingdom. Depending on whether you are cycling or flying, you will need your map to have a different set of symbols to depict different features and themes. These may include hotspots of mountainous areas if you’re cycling, or where the airports and routes are if you are flying. It’s this information that will inform your decision-making. Of-course, any map has to represent multiple perspectives, so a map usually consists of these multiple perspectives overlaid on top of each other.

In the same way, in an organisation, a set of symbols from a range of perspectives is needed for representing the risk landscape. This will help you turn risk data into risk information, to support informed decisions. This is where the risk map comes in.

What is a risk map?

Taking the definition of a map that we used earlier, a risk map is a way of representing the risk landscape using a set of symbolic categories for classifying those risks. These can cover themes or features that you are looking for in the risk landscape.

Just as the symbols you are interested in on the UK map will depend on whether you are cycling or flying, the symbols on your risk map will depend on the varying perspectives on risk within your organisation.

A comprehensive risk map will enable each part of your organisation to view risk from the perspective that best enables them to manage risks to their own objectives. For example, the HR function may be interested in risks pertaining to resource gaps or improving performance through better training and skills, while the board may be focussed on risks relating to the global economy.

The way that you want to categorise risks, and the detail of what you decide to put into your risk map will become critical to looking for risk hotspots, because it will give you a criteria against which to group, aggregate and relate risks. In the next sections we will look at how to decide on the composition of your risk map.

How do you decide what categories go into a risk map?

The key challenge is to create the right risk map for your business: one that will be understood and used, not only to help identify themes in current risk data, but also to help structure brainstorming for undiscovered threats and opportunities.

There are five important stages in establishing a risk map:

- Understand the objectives, context and targets of the organisation you are working in. If categories can’t be attributed against objectives, then it is likely that the risk hotspots you find will not tell you anything about what matters to your organisation.

- Review themes in past failures, successes and lessons learned. Look at where objectives have failed to be met in a similar context, and see if there are any trends that point towards common risk types.

- Elicit what management want to know. The risk reporting requirements (and hence perspective) of the board will drive part of the contents off the risk map. Often, you will need to help management understand what information will help them to make effective management decisions.

- Define a consolidated set of appropriate categories as elicited from the first three steps

- Communicate the defined categories across the management structure, ensuring that everybody understands what they are and how they are to be used.

To ensure implementation of the right risk map, responsibility must lie with someone in a position to successfully carry out all of these stages – the Chief Risk Officer. The task involves good communication with the relevant stakeholders, understanding their needs and getting buy-in.

In many respects, the final step is most important: even the best set of risk categories won’t deliver results unless they are filled in. The risk map could fall into disuse and the process of drawing out important information could become needlessly bureaucratic.

Some of the reasons that result in risk maps that aren’t fit for purpose are:

- Poor definition of the risk map, including who defines and owns elements of it.

- Lack of understanding of the categories by stakeholders who are identifying risks. This can lead to incorrectly classified risks, and therefore a risk map that provides no value.

- A lack of buy-in when filling risk categories in, either because categories are not relevant or appropriate to the stakeholders, or due to a lack of visibility of how filling them in will help risk management.

Aligning the risk map against objectives

We have already established that the first place to look for categories to go into the risk map is your set of objectives. However, to distill a set of appropriate categories that relate to your objectives can seem like a difficult task.

Instead, try looking at what the Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) for those objectives are. You can then start to engage stakeholders to provide information about what risk categories would be useful against those KPIs.

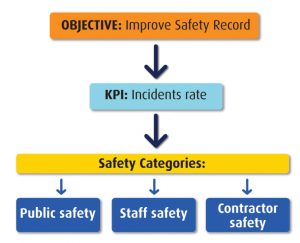

Figure 4: Example of eliciting categories from objectives

For example, say you are working for an airline company that wants to improve its safety record. First, you need to decide how the performance against this objective will be measured (a set of KPIs). In this case, you could sensibly measure whether the safety record is improving by monitoring the incident rate, so you could choose to use that as the KPI for the objective.

With the KPI established, think about what information would be useful in identifying risk hotspots. Management may decide that the Safety function should focus on public safety as the primary concern. They may wish to categorise risks according to whether they are related to the safety of the public, contractors or staff. This will let you look for types of safety risk hotspots to focus management attention.

Figure 5: Example of eliciting categories from objectives

Similarly, the corporate objectives may include increasing market share, by increasing amount of new business won. This may be measured by the percentage of new business won compared to repeat business.

There might be a set of risk categories to help the marketing department look for risk hotspots, based what sorts of things attract new business. It would be good to know the threats and opportunities in those areas too!

This sort of structured thinking can help to elicit a useful set of risk categories that are appropriate to your organisation’s objectives. But remember, stakeholder engagement and communication are key to getting these categories right.

Using lessons learned to help define a risk map

One of the most important sources of information for a risk map is to learn from past mistakes and successes; for example, by looking at similar industries, projects, or past failures within your own organisation.

When things go wrong, it is (by definition) because threats have impacted. Similarly, when performance has exceeded expectations, opportunities may have been taken.

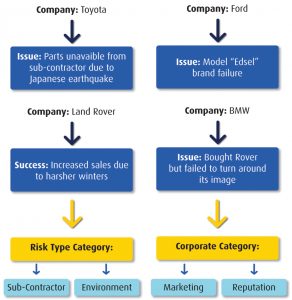

Figure 6: Example of eliciting categories from past experience

Looking at lessons learned, you can start to look for themes or types of risks that occur. You may start to notice that most of your projects fail because of problems with sub-contractors, or due to a common set of external factors. Including these as categories will not only help you to monitor whether these problems are recurring, it will also reinforce continuous improvement by ensuring that people consider what could go wrong in those areas. They should then be able to avoid issues rather than just respond to them when they occur.

Take the example of the car manufacturing industry. The figure at the bottom of page 4 gives examples of how real failures and could yield a useful risk map.

These overarching categories should then be broken down into meaningful components, in collaboration with the relevant people. So the marketing department should help to define specific marketing categories, and the procurement department should help to define a list of specific sub-contractors.

Using a risk map

Once you have defined the risk map and communicated it to all stake holders, it’s time to start putting it to use.

Its first use is to support the capture of risk data. The risk map should be used at risk identification workshops, not only to help categorise risks, but also act as a check-list to make sure you are considering risk sources that you may not have thought of otherwise. You then need a central risk repository, which supports consistent input of risks identified across the enterprise against risk map criteria. Commercial Off-the-shelf tools like Predict! are designed to be configured with ERM risk map information.

Once you have captured the right data, the risk map can be used to support information gathering for reporting and decision-making. Groups of risks defined against a risk map are invaluable in identifying and managing systemic risks, risk hotspots, and rolled up or aggregated risk. The map is a tool for finding where key risk exposure lies. Again, it is import that risks are stored in an ERM tool to support aggregation of the key risks which would not be visible from separate risk registers. This allows you to identify these trends and hotspots in any area of your business, or across the business as a whole.

Systemic risks

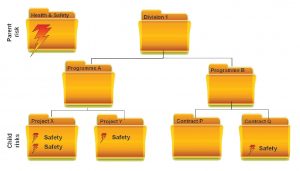

Systemic risks are similar or interdependent risks which affect many different parts of your organisation. A risk map allows similar risks across the organisation to be categorised under one heading, and for relationships to be found between those risks. It may be that some of those risks are in fact the same risk occurring many times in different areas, or that many stakeholders have identified the same opportunity across different parts of the organisation.

For example, in figure 7, a risk map has been defined to allow projects to categorise their risks as “Safety” risks. This will allow the safety manager to search the risk database specifically for safety. By looking at them more closely for patterns, it may emerge that many of them are the same risk. For instance, there may be a piece of safety-critical equipment that is the source of the same risk across lots of operations.

The safety manager could manage these risks as a family of risks, and relate them as children of a larger parent risk being managed by the Health and Safety function. This is cost effective, as managing the risks together will be more efficient than managing them individually without coordination, but perhaps more importantly it highlights an important problem that may otherwise have been missed. The risks may individually appear small, but together they could account for a lot of risk exposure.

Emerging risk hotspots

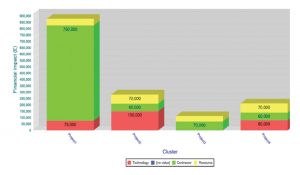

By running metrics across your risks based on their categorisation, you can start to look for risk hotspots across your organisation.

The example below is for an organisation that builds train carriages. You can see that for some reason, there is a lot of “Contractor” risk in Project 1, but there is no “Technology” risk in Project 3. This could be particularly interesting if you knew that those projects were very similar. What is causing so much contractor risk in Project 1? Are there technology risks that Project 3 has not thought of? A lack of information can stand out as a hotspot just as much of a big area of exposure.

Figure 8: A graph showing risk hotspots

By slicing and dicing your metrics data by organisational area against categories, you can start to look at what category of risks account for the most exposure, and start to see how different parts of the organisation compare to each other. Using this information, you can start to ask the right questions about risk. You can also start to look more closely at the causes of those hotspots.

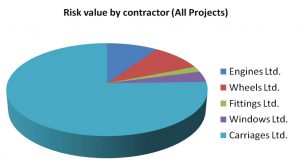

For example, if you have identified that contractors are a risk hotspot, you may decide to drill down into this area. The chart below reveals that for some reason, there is a lot of risk relating to a specific contractor. Once you know that, you can then start to look at individual risk values, and look at whether there are a lot of smaller risks or a smaller number of large risks driving this value.

Figure 9: Drilling down into risk hotspots

Financial aggregation

Figure 10: Aggregating financial exposure for IT risks

Risk maps can also be used as a filter overlaid onto your organisational structure. In the example below, the Finance function has been made aware that there is a lot of budget being attributed to risks categorised as “IT” risks in the organisation.

When reporting on this large IT risk exposure to the board, the risk map will allow you to paint a picture of how this exposure is spread across the organisation, and give you criteria with which to drill down to see what parts of the organisation are most exposed to IT related failure.

The benefits of a risk map

We have seen how to design and implement a risk map, and how it could be used. And yes, the risk map will help in the risk identification stage of the risk process, and assist in finding risk hotspots. But what are the benefits to the organisation as a result of this?

There are some hard benefits in terms of real cost savings.

Firstly, cost savings are achieved by reducing the amount of time and resource required to carry out risk management tasks. Risk identification workshops will be streamlined by having a risk map against which to brainstorm risks. Through having a more consistent set of risk data, the speed of turning that into real reporting information for decision-making from will be greatly reduced.

Then there are the direct cost savings of the risk map from the strategic decisions it allows management to make. By finding risk hotspots, mitigation budget can be targeted and key problem areas and efficiently centralised to address systemic risks. This saves the repetition of resource and budget against individual risks. And don’t forget that this will include deciding which opportunity hotspots to apply resource to.

Softer benefits are seen too. At enterprise level, the easy availability of information on trends and themes of risk rather than piecemeal information about individual ‘Top’ risks gives the board a better understanding of the risk landscape. Corporate governance becomes more effective through proactive risk response that is strategic, rather than being reliant on tactical, often knee-jerk reactions to producing risk based information. It will also help the board to be assured of good risk governance because the strategy addresses the right risk areas.

Finally, understanding of and confidence in the risk process is improved. Internally, this leads to increased buy-in to risk management, and so to more reliable data and continuous improvement. Externally, increased confidence means that the company’s standing is improved both with existing and potential customers, and with credit ratings agencies.

Conclusion

We have seen that one of the key challenges in establishing ERM is moving from having a very

Figure 11: Drawing together all of the risks that belong to a particular hotspot

large number of scattered and tactically managed risks, to having a management level understanding of the risk landscape of the organisation. Using a risk map overlaid onto the organisation structure, you can start to get an idea of where the key risk hotspots are located.

You can establish a useful symbolic risk map of categories to represent the risk landscape through the five stages of understanding objectives, looking at lessons learned, eliciting the right decision-making focus of management, then defining and communicating the resulting risk map.

A risk map takes an unruly set of risk data, structures it in a relevant and easily understood way, paving the way to better reporting and strategic management of risk hotspots. The result is better performance and confidence across the entire organisation.